Emerging States

The history of Germany between 1740 and 1788

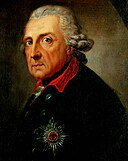

The dominant factor in 18th-century German history was undoubtedly the emergence of Prussia as the main rival to Austria, which had long been the leading state within the German empire. Prussia grewin stature for several reasons - through Frederick the Great's seizure of the rich province of Silesia, through the personal prestige acquired by Frederick himself, and through the vast gain of territory in the successive partitions of Poland. But certain other states were also be identified at this time as likely players in the struggles which will eventually lead, in the 19th century, to a united Germany.

Saxony began the 18th century as a very significant power. The state was weakened in subsequent decades, through disastrous involvement in Poland and because it was between the arch-rivals Prussia and Austria. Even so, Saxony's size and large population gave it an undeniable importance.

Hanover acquired an entirely new stature during the century, from the personal link with Britain after the elector succeeds to the British throne in 1714 as George I. In the wars of the 18th century Hanover had a special importance and exposure, as Britain's continental outpost.

Bavaria, ruled by the Wittelsbachs, had played a major role in German history from early medieval times. In recent centuries a division between two branches of the family had somewhat reduced its status. From 1329 the western region went its own way as the Palatinate of the Rhine. The split was accentuated in the Reformation, when the Palatinate becomes Protestant while Bavaria remains Roman Catholic.

The Palatinate returned to the Catholic fold in 1685, and by the end of the 18th century this line has recovered the entire inheritance. In 1777 the Bavarian line of the dynasty died out. The region was reunited under the rule of the Palatine branch.

Wars

In the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748) Maria Theresa fought successfully for recognition of her succession to the throne. But in the Silesian Wars and in the Seven Years' War she had to cede 95 percent of Silesia to Frederick the Great of Prussia. After the Peace of Hubertsburg in 1763 between Austria, Prussia and Saxony, Prussia won recognition as a great power, thus launching a century-long rivalry with Austria for the leadership of the German peoples.

In 1772–1795 Prussia took the lead in the partitions of Poland, with Austria and Russia splitting the rest. Prussia occupied the western territories of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that surrounded existing Prussian holdings. This occupation led over a century of Polish resistance until Poland again became independent in 1918.

Culture and Enlightenment

Before 1750 the German upper classes looked to France for intellectual, cultural and architectural leadership; French was the language of high society. By the mid-18th century the Enlightenment had transformed German high culture in music, philosophy, science and literature. Christian Wolff (1679–1754) was the pioneer as a writer who expounded the Enlightenment to German readers; he legitimized German as a philosophic language. German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under composers Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791).

In remote Königsberg philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom, and political authority. Kant's work contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought – and indeed all of European philosophy – well into the 20th century.

The German Enlightenment won the support of princes, aristocrats, and the middle classes, and it permanently reshaped the culture.

From 1763, against resistance from the nobility and citizenry, an "enlightened absolutism" was established in Prussia and Austria, according to which the ruler governed according to the best precepts of the philosophers. The economies developed and legal reforms were undertaken, including the abolition of torture and the improvement in the status of Jews. Emancipation of the peasants slowly began. Compulsory education was instituted.

References: Wikipedia, Historyworld.net