Weimar Republic

History of Germany between 1919 - 1932

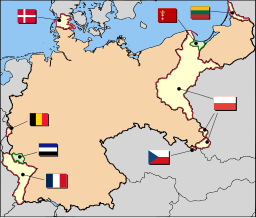

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The greatest enemies of democracy had already been constituted. In December 1918, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was founded, and in 1919 it tried and failed to overthrow the new republic. Adolf Hitler in 1919 took control of the new National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), which failed in a coup in Munich in 1923. Both parties, as well as parties supporting the republic, built militant auxiliaries that engaged in increasingly violent street battles. Electoral support for both parties increased after 1929 as the Great Depression hit the economy hard, producing many unemployed men who became available for the paramilitary units.

The early years

On 11 August 1919 the Weimar constitution came into effect, with Friedrich Ebert as first President. In the first months of 1920, the Reichswehr was to be reduced to 100,000 men, in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles. This included the dissolution of many Freikorps – units made up of volunteers. In an attempt at a coup d'état in March 1920, the Kapp Putsch, extreme right-wing politician Wolfgang Kapp let Freikorps soldiers march on Berlin and proclaimed himself Chancellor of the Reich. After four days the coup d'état collapsed, due to popular opposition and lack of support by the civil servants and the officers. Other cities were shaken by strikes and rebellions, which were bloodily suppressed.

Germany was the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the new Soviet Union. Under the Treaty of Rapallo, Germany accorded the Soviet Union de jure recognition, and the two signatories mutually cancelled all pre-war debts and renounced war claims.

When Germany defaulted on its reparation payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the heavily industrialised Ruhr district (January 1923). The German government encouraged the population of the Ruhr to passive resistance: shops would not sell goods to the foreign soldiers, coal-mines would not dig for the foreign troops, trams in which members of the occupation army had taken seat would be left abandoned in the middle of the street. The passive resistance proved effective, insofar as the occupation became a loss-making deal for the French government. But the Ruhr fight also led to hyperinflation, and many who lost all their fortune would become bitter enemies of the Weimar Republic, and voters of the anti-democratic right. See 1920s German inflation.

In September 1923, the deteriorating economic conditions led Chancellor Gustav Stresemann to call an end to the passive resistance in the Ruhr. In November, his government introduced a new currency, Reichsmark, together with other measures to stop the hyperinflation. In the following six years the economic situation improved. In 1928, Germany's industrial production even regained the pre-war levels of 1913.

Great depression

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 marked the beginning of the worldwide Great Depression, which hit Germany as hard as any nation. In July 1931, the Darmstätter und Nationalbank – one of the biggest German banks – failed. In early 1932, the number of unemployed had soared to more than 6,000,000.

On top of the collapsing economy came a political crisis: the political parties represented in the Reichstag were unable to build a governing majority in the face of escalating extremism from the far right (the Nazis, NSDAP) and the far left (the Communists, KPD). In March 1930, President Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning Chancellor. To push through his package of austerity measures against a majority of Social Democrats, Communists and the NSDAP (Nazis), Brüning made use of emergency decrees and dissolved Parliament. In March and April 1932, Hindenburg was re-elected in the German presidential election of 1932.

The Nazi Party was the largest party in the national elections of 1932. On 30 January 1933, pressured by former Chancellor Franz von Papen and other conservatives, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor.

Science and culture

The Weimar years saw a flowering of German science and high culture, before the Nazi regime resulted in a decline in the scientific and cultural life in Germany and forced many renowned scientists and writers to flee. German recipients dominated the Nobel prizes in science. Germany dominated the world of physics before 1933, led by Hermann von Helmholtz, Joseph von Fraunhofer, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Werner Heisenberg. Chemistry likewise was dominated by German professors and researchers at the great chemical companies such as BASF and Bayer and persons like Fritz Haber. Theoretical mathematicians included Carl Friedrich Gauss in the 19th century and David Hilbert in the 20th century. Carl Benz, the inventor of the automobile, was one of the pivotal figures of engineering.

Among the most important German writers were Thomas Mann (1875–1955), Hermann Hesse (1877–1962) and Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956). The pessimistic historian Oswald Spengler wrote The Decline of the West (1918–23) on the inevitable decay of Western Civilization, and influenced intellectuals in Germany such as Martin Heidegger, Max Scheler, and the Frankfurt School, as well as intellectuals around the world.

After 1933, Nazi proponents of "Aryan physics," led by the Nobel Prize-winners Johannes Stark and Philipp Lenard, attacked Einstein's theory of relativity as a degenerate example of Jewish materialism in the realm of science. Many scientists and humanists emigrated; Einstein moved permanently to the U.S. but some of the others returned after 1945.

Reference: Wikipedia

Previous historical period: German Empire (1867-1918) | Next historical period: Nazi Germany (1933-1945)